Just in time for your midsummer celebrations, we have an exhibition review for you: The exhibition Robert Capa: The Photojournalist, curated by Gabriella Csizek, shows approximately 150 photographs from the Master Collection. Capa’s most famous photographs can be seen here including a considerable number of images taken during the Spanish Civil War and some of the famous photographs from the Allied D-Day landings in Normandy on 6 June 1944. Often, Capa was not only a witness but also a participant taking pictures in extraordinarily dangerous circumstances, which supported both the authenticity of his images and his influential claim that proximity to action is an essential ingredient of photojournalism.

Capa was born in Budapest on 22 October 1913 as Endre Friedmann. He emigrated first to Berlin in 1931, then in 1933 to Vienna. After staying there for six months, he returned to Budapest and later that year moved to Paris. One year later, he changed his name to Robert Capa.

In 1939, he visited his mother in New York and stayed there, despite difficulties stemming from his status as enemy alien after the United States had entered the war. However, a return to Europe was obviously impossible for a left-wing photographer with Jewish origins. After the war, Capa was granted US citizenship.

In the exhibition, Capa’s work is not shown in isolation but accompanied by information spaces informing visitors of Capa’s childhood, the city where he grew up (Budapest) and the publication and dissemination process of photographs at the time.

In addition to the images, the exhibition features, among other things, an installation of the Mexican Suitcase which was lost since 1939 and rediscovered in Mexico City almost seventy years later – a photographic sensation (see Young 2010).

This suitcase contained approximately 4,000 negatives from Capa, David Seymour (Chim) and Gerda Taro but not what arguably is the most famous photograph from the Spanish Civil War, Capa’s Death of a Loyalist militiaman, Cerro Muriano, Córdoba front, Spain, September 5, 1936, aka The Falling Soldier (see Susperregui 2016).

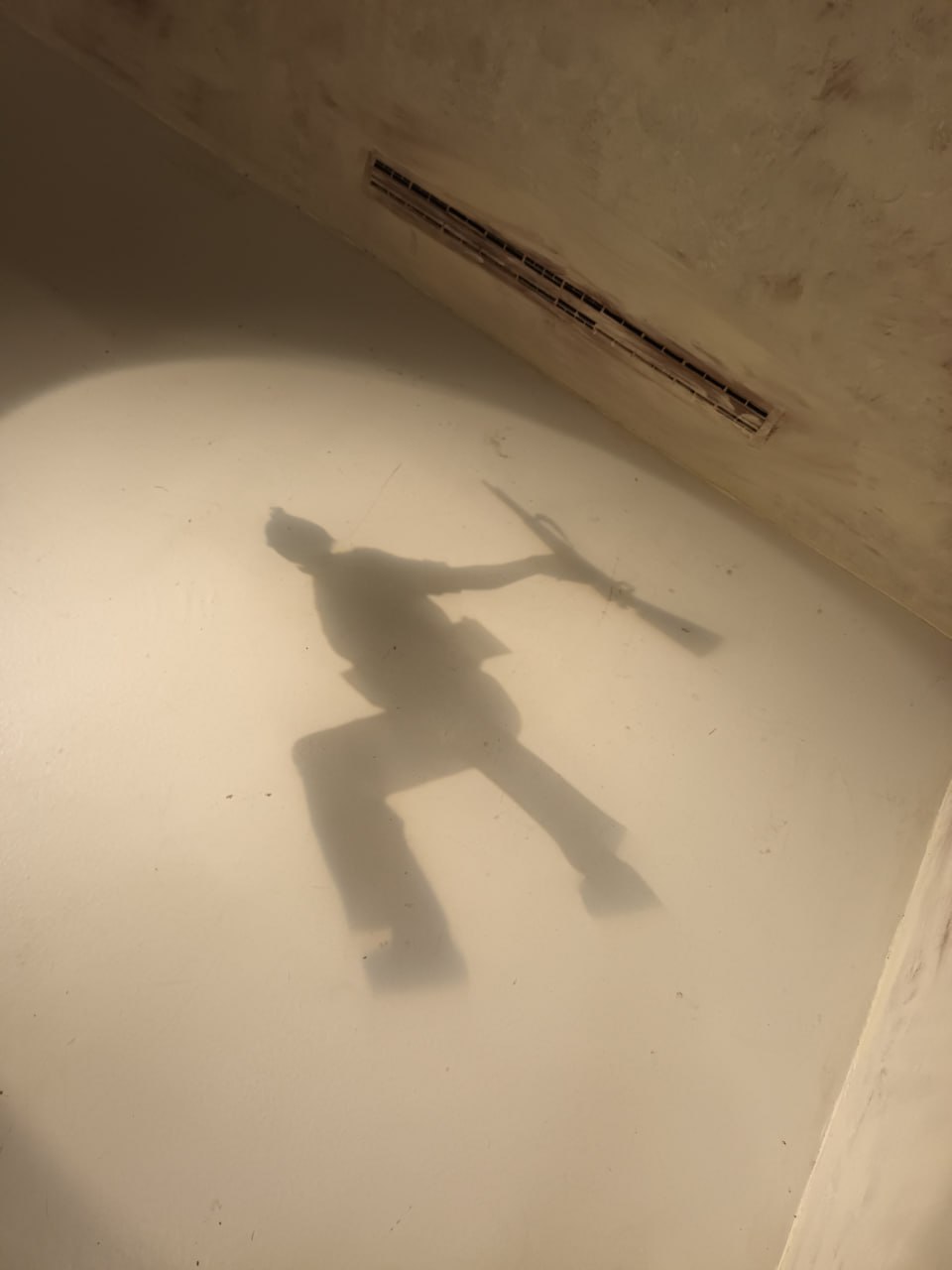

This photograph is included in the exhibition just as is the March 1938 photograph Boy soldier, Hankou, China, which appeared prominently on the cover of Life. Also on display in the exhibition is the last photograph Capa took before he was killed by stepping on a landmine on 25 May 1954, Minesweepers carrying metal detector and soldiers of the French convoy walking in the field on the road from Nam Dinh to Thai Binh, Vietnam.

Capa was what is conventionally designated a war photographer, but he was also both an aftermath photographer and a photographer of everyday life. It is indeed laudable that the exhibition presents Robert Capa, the photojournalist, rather than limiting his work to that of a war photographer.

For example, his oeuvre includes a huge number of photographs of everyday life taken in the Soviet Union while visiting the country in 1947 with the writer John Steinbeck (Steinbeck 1999; see also our blog post on Steinbeck’s Russian Journal) and numerous aftermath pictures taken in Berlin in the autumn of 1945 (see Schütz 2020).

His photograph American soldier killed by a German sniper, Leipzig, Germany taken on 18 April 1945 also shows how difficult it sometimes is to clearly distinguish war from its aftermath. As Robert Whelan explains, the photograph was published in Life on 14 May 1945 at which time the war in Europe was already over and its aftermath had started (Whelan 2007: 254).

While photographic greatness is often assigned to Capa’s war photographs, the quality of the photographs Capa took in other, more peaceful circumstances reminds visitors that such greatness is a social construction, contingent, changeable and adaptable to all sorts of circumstances.

Seen in this light, Capa’s 1932 photographs of Leon Trotsky lecturing in Copenhagen are equally great, if by ‘great’ we mean images that make viewers engage with the image and the conditions it depicts, lingering and remaining alive in viewers’ pictorial memories.

Capa’s influence on the evolution of photojournalism was, and still is, tremendous, both through his own work and through Magnum Photos, the famous group of independent photographers which he proposed to create in 1947.

The exhibition is beautifully and respectfully presented on two floors of the historical Ernst House, built in 1912 by the art collector Lajos Ernst (see https://capacenter.hu/en/ernst-house/), thus combining the history of architecture with the history of photojournalism in a unique way, inviting visitors to reflect on both.

We wish you and your family and friends a relaxing and pleasant summer break.

Hyvää juhannusta!

The overall context of Hungarian photographers working in the United States of America can be seen at the exhibition Kertész, Moholy-Nagy, Capa … Hungarian Photographers in America (1914 – 1989) at the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest.

Robert Capa: The Photojournalist is at the Robert Capa Contemporary Photography Center, 8 Nagymező Street, 1065 Budapest.

More information: https://robertcapaexhibition.capacenter.hu/en/

References

Schütz, Chana (ed.), Robert Capa: Berlin Sommer/Summer 1945 (Berlin: Salzgeber, 2020).

Steinbeck, John, A Russian Journal. With photographs by Robert Capa. With an introduction by Susan Shillinglaw (London: Penguin, 1999).

Susperregui, José Manuel, The Location of Robert Capa’s Falling Soldier. Communication & Society 29(2), 2016: 17–43.

Whelan, Richard, This Is War! Robert Capa at Work (New York: International Center of Photography/Göttingen: Steidl, 2007).

Young, Cynthia (ed.), The Mexican Suitcase: The Rediscovered Spanish Civil War Negatives of Capa, Chim, and Taro. Volumes 1 and 2 (New York: International Center of Photography/Göttingen and Steidl, 2010).

Photographs taken at the exhibition for strictly informational and non-commercial purposes.