Despite the ‘pictorial turn’ in peace studies, integrating visual research methods remains challenging.[i] Academia seems hesitant to put the visual at the heart of its endeavors. Scholars tend to ‘capture’ and categorize meanings by ‘reading images’ instead of allowing themselves to be ‘captured by’ the image and its evocative and imaginative potential.[ii] The image as data, however, demands the researcher to first ‘sit’ with the image and question which certainties might be disrupted. We often approach the image as text, while visual analysis may require alternative methodological steps and reporting techniques.[iii] It is important to ask: ‘What does the image do to us?’ Instead of: ‘How can we label it?’.

Comparable questions apply when we aim to engage the public as processers of visual representations of peace. ‘Active looking’ is described as an essential attitude when we wish to let images of peace ‘sink in’, especially when they are produced in different contexts.[iv] This blog shares preliminary observations of engaging audiences with existing visual representations of peace as part of a participatory ‘experiment’ at a Dutch science festival (Betweter Festival 2023).[v] It builds onto the earlier blog “This is supposed to look like a dove: engaging the public, visualizing peace”, also published on this website.

Depth of visual peace literacy

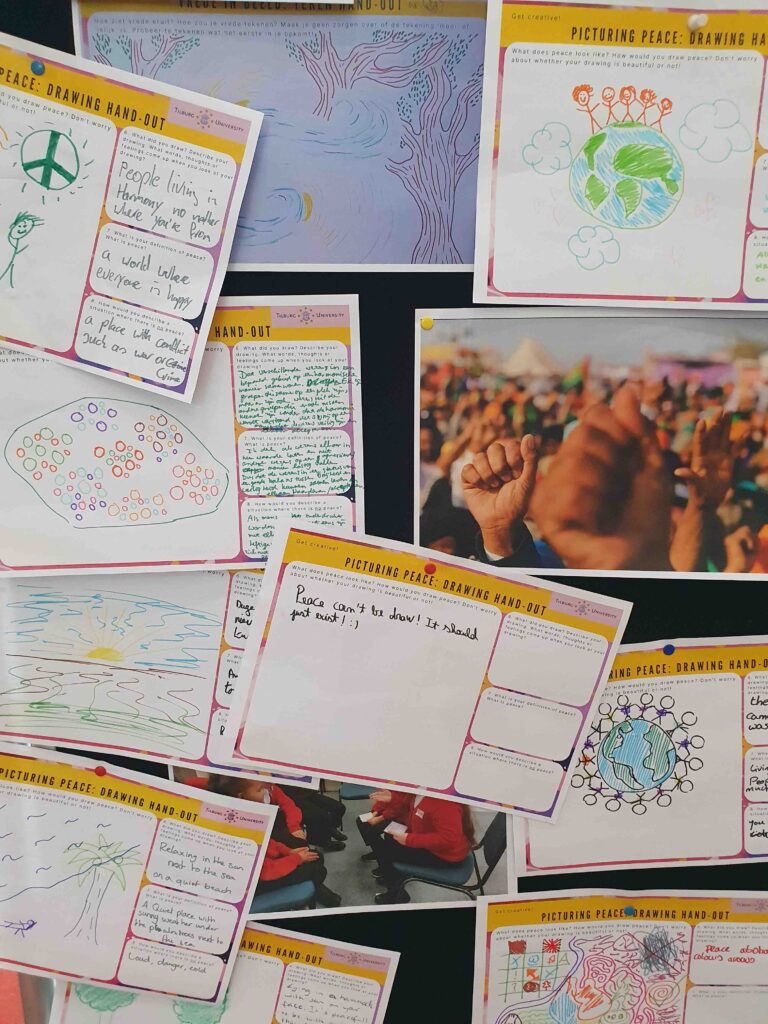

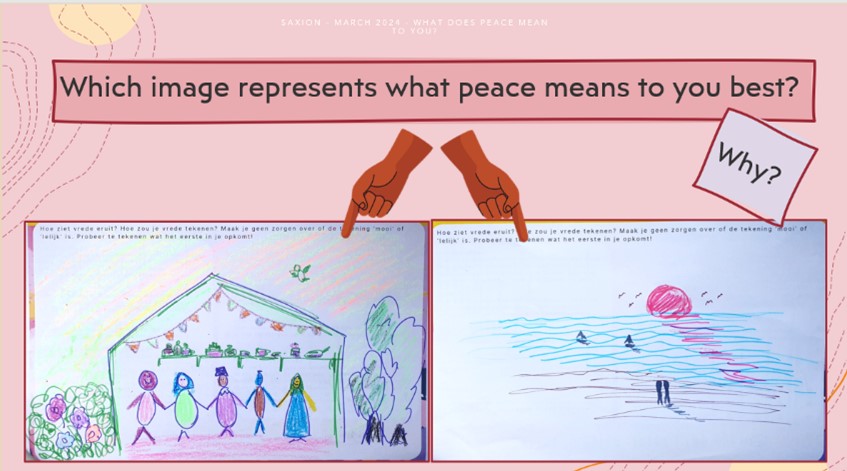

Next to the 120 science festival visitors who drew peace, another 60 participants chose to join the ‘image game’, a digital survey where visitors selected which existing peace image suited their understanding of peace best.[vi] Four image categories were mixed: 1) peace symbolism 2) mainstream peace visuals from search engines 3) images corresponding to theoretical aspects of peace[vii] and 4) Everyday Peace Indicators photographs made by rural Colombian communities.[viii] With the image game, we intended to find out which visuals come closest to people’s associations with peace. We wondered whether everyday peace photographs resonate across contexts, using survey questions where respondents had to fill in captions and write down their first thoughts about the peace photographs presented (see image 1).[ix]

Most people picked mainstream existing peace imagery as their ‘top’ visualizations of peace (see image 2). Still, their textual descriptions of these images display rich individual differences. The interpretations give insight into the many ways the viewer sees visual representations of peace and the peace concept as a whole. The dialogue between the image and the viewer seems to be not in ‘isolation’ but in relation: to other visuals presented before, broader societal narratives of peace, collective memories, emotions attached to conflict and the resolution thereof, and ideals for peaceful futures (see example image 3). Some participants simply reason: “I picked this image (of peace symbols) because these are the symbols that represent peace to me” which questions the depth of the public’s visual literacy of peace. There is a paradox here, as the diverse interpretations most viewers gave of the same ‘mainstream’ peace images, do ask us to revise some assumptions related to the restraining character of popular peace symbols and their ability to foster plural peace perspectives.

Teleporting everyday peace photographs

The everyday peace photographs (image category 4 of the image selection game, initially presented without captions) produced by the Colombian rural communities were least chosen by the festival visitors and only picked when displaying clear and recognizable depictions (e.g. nature or education). This confirms our expectation that working with everyday peace photographs to engage people and ‘open up’ visual peace literacy, can be better presented in a more interactive participatory design. The limited extent to which the Colombian images resonate in the Dutch context may relate to the personal way in which people process images as well as the specific context the images were created in, by people who experienced conflict directly. In a more interactive environment between the researcher and the respondent, the viewer may be better equipped to respond to contextualized information. A deeper engagement and conversation with the images presented may result in ‘co-creating’ and potentially reformulating one’s imagination of peace.[x]

To look ‘actively’ needs a slower pace format. During a follow-up experiment at a Dutch University for Applied Sciences (see image 4), I noticed how curious and willing students were to discuss peace. When they were daunted by the drawing task or hesitant to give their immediate opinion, it helped to let them collaborate, look at other drawings, and create visual peace through conversations.[xi] The classroom is a suitable setting for a repetition of the image game (see image 5) but through guided reflective exercises. In this context, earlier produced peace drawings can be integrated to extend the body of visual representations and to challenge mainstream peace visuals. Lastly, many existing images might even ‘become’ new representations of peace. Asking students: ‘What image on your phone depicts what peace means to you’ may give new insights into how visuals and understandings of peace intersect.

The researcher as curator

During an earlier try-out in my neighborhood, I asked neighbors of a vibrant street to visualize what everyday peace means to them.[xii] It felt, however, as if I was extracting drawings as ‘objects’, interrupting citizens from their daily routines. A young man responded: “Why do you ask me?”. The follow-up conversation highlighted the importance of providing a platform for underrepresented voices of peace. It also resulted in the question of why I was not subjecting myself to the same research endeavor. By producing peace photographs of the same neighborhood myself, the complexity of the research questions became clearer. It also gave depth to my understanding of how everyday utterances of violence and peace can exist simultaneously, even in a so-called peaceful society (see image 6).

The example shows the importance of remaining critical of the peace images we use or ‘extract’ in our research. The images we selected for the image game to correspond with academic peace definitions, were interpreted differently by the festival visitors. This not only points out the rich differences in visual processing but also questions the suitability of a visual ‘classification’ approach. Is it possible to match existing visuals that assumingly relate to theoretical definitions of peace? By whom and for what purpose? What does this method do to the width of the visual peace landscape, including certain visuals and excluding others? When does the curation of images by the researcher (or educator) help to ‘open’ up dialogue around alternative visual representations of peace and when does it constrain agency? If visual imaginations of peace are multifaceted, then an image selection game to select the visual out of a curated selection of images might be too constraining. The initial aim to provide a platform for underrepresented imaginations of peace then may unintendedly hinder the emergence of new visual representations of peace or accelerate undesired power dynamics between the researcher and the ‘researched’.[xiii]

About the author:

Dagmar Punter is a PhD candidate at the Department of Communication and Cognition at the Tilburg School of Humanities and Digital Sciences, The Netherlands. Her research project ‘What does peace mean to you?’ explores how the public defines, imagines, and visualizes peace. She is currently conducting a cross-national survey on which factors impact people’s peace norms and values and whether social representations of peace differ across contexts. She holds an MSc in Conflict Resolution and Governance and a BSc. in Political Science from the University of Amsterdam. Other research interests are emotions in political discourse, creative approaches to conflict resolution and mediation, civic education, and public engagement around controversial topics.

Comments and ideas responding to this blog are welcome and can be emailed to d.e.punter@tilburguniversity.edu

[i] Spencer, S. (2022). Visual research methods in the social sciences : awakening visions (Second). Routledge; Bellmer, R., & Möller, F. (2023). Peace, complexity, visuality : ambiguities in peace and conflict (Ser. Rethinking peace and conflict studies). Palgrave Macmillan.

[ii] Inspiration for this phrasing comes from the interactive workshop ‘Moving images of violence’ for PhD-researchers organized by the University of Amsterdam together with dr. Daniele Rugo.

[iii] Bleiker, R. (2015). Pluralist methods for visual global politics. Millennium, 43(3), 872–890. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0305829815583084

[iv] Bellmer, & Möller. (2023). Active looking: images in peace mediation. Peacebuilding, 11(2), 136–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/21647259.2022.2152971

[v] To get an impression of the science festival: https://www.betweterfestival.nl/ In the experiment ‘What is peace?’ (‘Wat is vrede?’ in Dutch) festival visitors could decide to fill in a peace drawing hand-out or join the ‘image game’ where they select existing peace visuals that resonate most with their views of peace, including photographs created within the Everyday Peace Indicators Photovoice project in collaboration with dr. Tiffany Fairey (Kings College). For more information: https://www.everydaypeaceindicators.org/photovoice-in-colombia

[vi] Another 120 visitors made peace drawings, discussed in blog 1: Punter (2024) “This is supposed to look like a dove”: engaging the public, visualizing peace’. https://www.imageandpeace.com/

[vii] Image categories based on academic peace definitions were: 1) peace as the absence of war, 2) peace as conflict resolution or cooperation, including peace agreements, 3) peace as justice or rule of law, 4) peace as social-economic development, 5) peace as personal peace or inner calmness, 6) peace as (individual) freedom, 7) peace as political institutions, 8) peace as harmonious relationships or coexistence between people(s), 9) peace as norms and values or the establishment of a culture of peace, 10) peace as order and stability, 11) peace as (policy) intervention, 12) peace as struggle or resistance.

[viii] The everyday peace images were selected in collaboration with dr. Tiffany Fairey. For more insights on the value and proceedings of photovoice read: Fairey, T., Cubillos, E., & Muñoz, M. (2023). Photography and everyday peacebuilding. Examining the impact of photographing everyday peace in Colombia. Peacebuilding. https://doi.org/10.1080/21647259.2023.2184099 or her earlier blog for Image & Peace: https://www.imageandpeace.com/2021/11/11/participatory-community-and-citizen-photography-as-peace-photography/#_ftn2

[ix] For both the drawing exercise and image game participants at the festival were asked to write down how they would define peace as well as a situation where there is no peace, and respond to general statements such as ‘I often worry about the potential threat of war, I perceive the Netherlands to be a peaceful country, I find it important that peace is achieved’ and ‘war is sometimes justified to achieve peace’. In addition, visitors were asked to fill in general questions related to conflict news consumption, how vivid personal experiences and memories of violent conflict and war are for them, and demographics.

[x] Möller, F., & Bellmer, R. (2023). Interactive peace imagery – integrating visual research and peace education. Journal of Peace Education, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/17400201.2023.2171374

[xi] See for an impression (in Dutch): https://youtu.be/XlHvigbyb1s

[xii] Link to the Story Map (Punter 2022) ‘Everyday Peace in the Kanaalstraat. Imagining Peace in Lombok – Utrecht’: https://arcg.is/zznjf

[xiii] To read more about how visual participatory projects may aspire to enable social change while their actual outcomes may hinder giving ‘voice’ to underrepresented peace imaginations: Fairey, T. (2018). Whose photo? Whose voice? Who listens? ‘Giving,’ silencing and listening to voice in participatory visual projects. Visual Studies, 33(2), 111–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/1472586X.2017.1389301