At the time of writing more than 26.000 black and white ‘Peace Now’ posters are spread and attached to public spaces across the Netherlands. The organizers of the initiative, which started in the ‘peace city’ Utrecht, describe the free poster (image 2) as a ‘positive conversation starter’ in the context of increasing polarization.[i] Citizens are, by making the peace sign visible, enabled to express their feelings of powerlessness and ‘wishes for the world’, while wars at a distance continue to rage. According to its makers, the black and white colors represent current societal contrasts. The bold lines also shape the dove and olive branch, two popular examples of peace symbolism. The font of the poster recalls memories of the ‘60s and ‘70s anti-war protests.

What peace is visualized?

The initiative exemplifies how ‘ordinary citizens’ may become active contributors to the visual landscape of peace. The representation of the dove and olive branch, however, makes us wonder what kind of peace people are advocating for and, potentially, to which instances of violence they are responding.[ii] While mainstream peace visualizations like the white dove, holding hands, and the victory and peace sign, might be familiar to the public, less is known about the range and liveliness of alternative visual representations of peace among ‘ordinary citizens’. Furthermore, little research is available on whether these peace visuals come with alternative understandings of the peace concept itself.[iii]

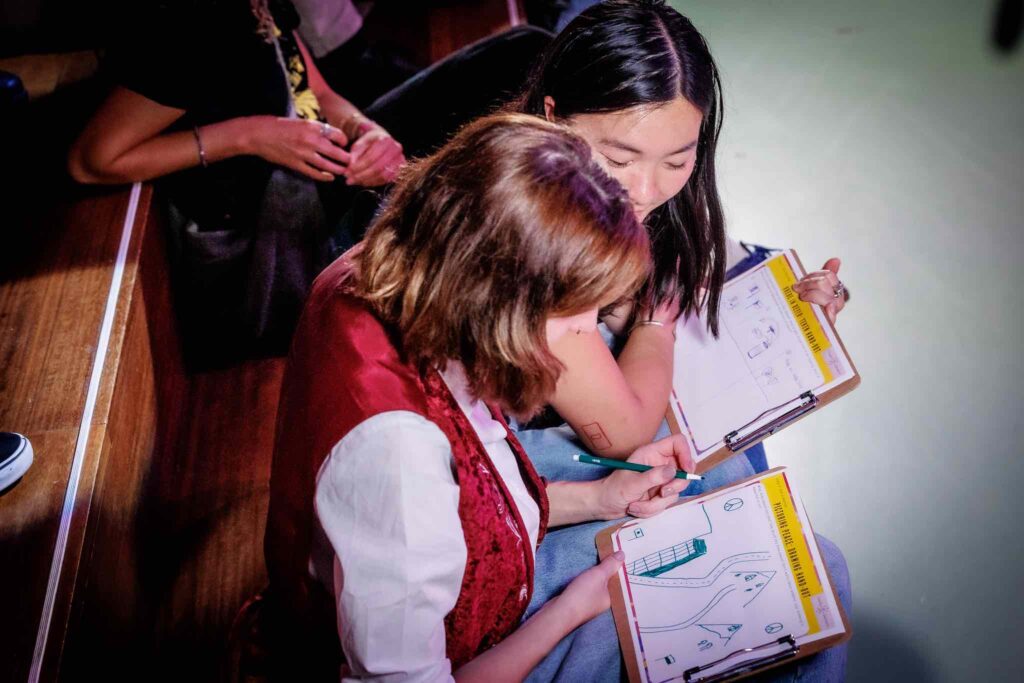

This contribution spread across two blogs, points out some pivotal questions related to visual literacy, visual peace production, public engagement, and interpreting peace visuals in the context of a peaceful society. It discusses preliminary observations of visual peace data (drawings, discussed in the first blog, and an image selection game of existing peace imagery, discussed in the second blog), conducted via a participatory ‘experiment’ at a Dutch science festival (see image 1, Betweter Festival 2023, Utrecht).[iv]

Drawing peace: personal, emotional, and relational

As most research working with peace drawings is conducted in the (post-)conflict setting, mostly with groups of children and students, doubts emerged at the design stage of the festival activities.[v] Are people living in a so-called ‘peaceful society’ able to reason what peace means to them, assuming they have little experience with the absence thereof? Are people curious enough to work their imagination? Are adults willing to participate in drawing exercises, moving from their mental imagery and associations to concrete representations on paper?[vi] How strong will dominant narratives and symbols of peace be in the responses we receive? And does this participatory ‘experiment’ help to unlock awareness around this very abstract concept?

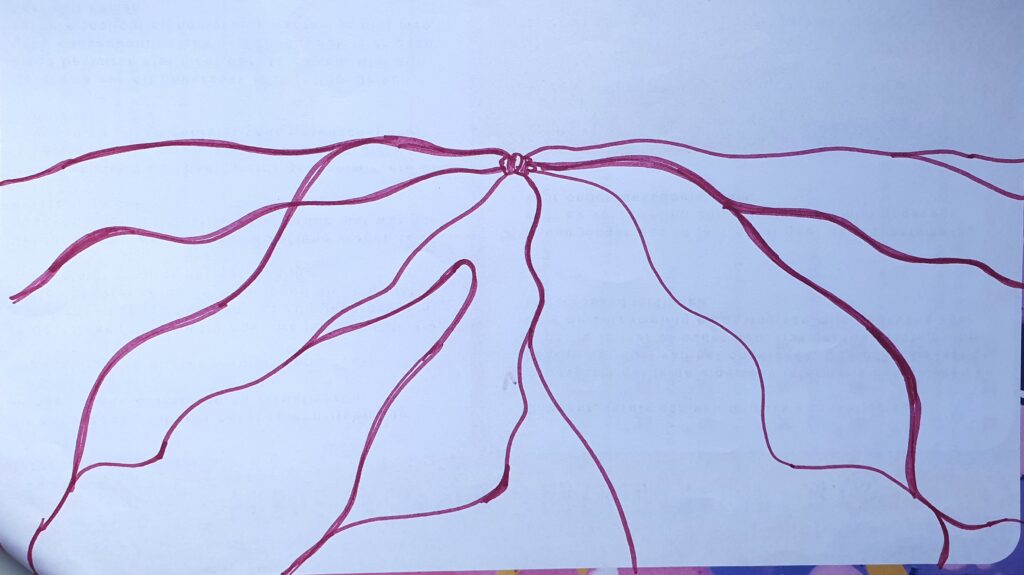

Uncertainties dissolved when looking at the approximately 120 drawings collected that evening (such as image 4). Only a fraction of visitors found it difficult to draw what peace means to them. This blog shares a few surprising observations concerning the collected materials. A selection of drawings purely shows abstract lines, curves, and shapes (see image 3). Some respondents commented that they perceived their visualizations to be unrealistic, representing ideal worlds, accompanied by expressions of sadness due to the perceived unfeasibility of their imagined peace.

People’s peace drawings, in contrast to people’s textual definitions of peace, are largely absent of negative peace representations (peace as the absence of war). Most peace drawings display elements of ‘small peace’, referring to harmonious relations between people, the coexistence of differences, and peace with nature or with(in) oneself. The drawings seem to correspond only minimally with definitions of peace involving (democratic) institutions, the rule of law, and peace agreements between state entities (top-down conceptions of peace). A large number of references to nature and a lack of common peace symbols display the potential and imaginative power of visuals of peace and the multifaceted nature of the associations that arise with the concept. The frequent display of people, faces, and holding hands, hint at peace perceptions that emphasize relational aspects of peace. The fact that these faces display smileys, questions to what extent understandings of peace are experiential and emotional. A further dive into the textual descriptions presenting first associations, including feelings, (such as in image 4) may give more insight into the nexus between emotions and the personal experience of peace.

Imagining peace: uplifting paralyzed societies

Engaging the public to construct their views of peace on paper seems to generate endless combinations of lines and meaning, displaying the multifaceted character of peace visualizations. Peace, thus, means different things to different people. And who you ask, and in which context, matters. This is an important message, as academic definitions and peace narratives in policymaking, seem to still relate mostly to top-down, state-centered, and negative peace. Moreover, the activity itself, translating peace imaginations on paper, results in tangible tools for reflective conversations, within the maker, between the drawing and its textual descriptions, and between the producer and viewer of these materials.

“Consciously setting out to create mental images of better futures so that these images might in themselves be uplifting to the spirit and empower otherwise paralyzed societies to action” is what Elise Boulding described to be crucial in challenging times.[vii] Asking audiences to first draw, then describe what they drew, and define what peace (and no peace) means, creates interesting intersections between how people perceive the concept versus how they experience peace in their everyday lives. Making lines visible on paper fosters the embodiment of the numerous ways in which people imagine peace. As Boulding argued a while ago – to create or sustain peace we might first need to actively engage in ‘seeing’, recognizing, and ‘re-envisioning’ it. Engaging the public to move from their mental images of peace to producing actual visuals could therefore be a small but required step in making peaceful futures more imaginable.

About the author:

Dagmar Punter is a PhD candidate at the Department of Communication and Cognition at the Tilburg School of Humanities and Digital Sciences, The Netherlands. Her research project ‘What does peace mean to you?’ explores how the public defines, imagines, and visualizes peace. She is currently conducting a cross-national survey on which factors impact people’s peace norms and values and whether social representations of peace differ across contexts. She holds an MSc in Conflict Resolution and Governance and a BSc. in Political Science from the University of Amsterdam. Other research interests are emotions in political discourse, creative approaches to conflict resolution and mediation, civic education, and public engagement around controversial topics.

Comments and ideas responding to this blog are welcome and can be emailed to d.e.punter@tilburguniversity.edu

[i] Based on the web-article: https://vredessite.nl/nieuws/peace_2196.html

[ii] “(..) the act of imagining peace (through film) is always specific, a particular resistance to a particular violence” in: Filmmaking, Violence and the Imagination of Peace (24-11-2020) by Daniele Rugo and Abi Weaver.

[iii] To read more about the visual landscape of peace: Engelkamp, S., Roepstorff, K., & Spencer, A. (2020). Visualizing Peace – The State of the Art. Peace & Change, 45(1), 5–27. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/pech.12384

[iv] To get an impression of the science festival: https://www.betweterfestival.nl/ In the experiment ‘What is peace?’ (‘Wat is vrede?’ in Dutch) festival visitors could decide to fill in a peace drawing hand-out or join the ‘image game’ where they select existing peace visuals that resonate most with their views of peace, including photographs created within the Everyday Peace Indicators Photovoice project in collaboration with dr. Tiffany Fairey (Kings College). For more information: https://www.everydaypeaceindicators.org/photovoice-in-colombia

[v] Examples are: Walker, K., Myers-Bowman, K. S., & Myers-Walls, J. A. (2003). Understanding war, visualizing peace: Children draw what they know. Art Therapy, 20(4), 191–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2003.10129605 & Jabbar, S., & Betawi, A. (2019). Children express: war and peace themes in the drawings of Iraqi refugee children in Jordan. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 24(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2018.1455058

[vi] In the book Picturing Research: Drawing as Visual Methodology (2011: 20) Mitchell et al. confirm the value of using drawing as a methodology to uncover adults personal lifeworlds: “We believe that the use of drawings is also appropriate for getting at the memories, thoughts, and feelings of adults—and that sometimes it is that quick request to ‘Draw. Quickly, just draw. Draw the first thing you think of.’ that captures something that is not easily put into words.”

[vii] Boulding, E. (1991). The challenge of imagining peace in war time. Conflict Resolution Notes. 8(4). Pp. 34-36.