“I saw and approached the hungry and desperate mother, as if drawn by a magnet. I do not remember how I explained my presence or my camera to her, but I do remember she asked me no questions. … She told me her age, that she was 32. She said that they had been living on frozen vegetables from the surrounding fields, and birds that the children killed. She had just sold the tires from her car to buy food. There she sat in that lean-to tent with her children huddled around her, and seemed to know that my pictures might help her, and so she helped me. There was a sort of equality about it.” (SOURCE: Dorothea Lange, Photographs of a Lifetime, New York: Aperture, 1982, p. 76)

The story is well known. On assignment for the Farm Security Administration, a US government agency, Dorothea Lange and several other photographers set out in the 1930s to document poverty and destitution in Oklahoma, Texas, Kansas, Colorado and New Mexico, those US states most affected by the Dust Bowl: vast dust clouds darkening the sky and triggering mass migration.

Such pictures were needed to obtain continuing support for the New Deal among a population that traditionally assumed a rather skeptical attitude to interventionist politics.

Pictures of victims in need of help from others were required and photography duly delivered, in the process not only “portray[ing] victims” but, as Jay Prosser notes, also “creat[ing] them” (2005, p. 90).

Lange’s photograph The Migrant Mother made both the photographer and Florence Thompson, the subject depicted, famous. The “sort of equality” that Lange identified in her interaction with Thompson, however, was anything but equal: Although Lange “made little direct profit” from the photograph (Company 2018, p. 25), she undoubtedly built her career on it; Thompson, however, for a long time “remained in public discourse the anonymous ‘Migrant Mother’” (Möller 2019, p. 218) devoid of agency, seemingly incapable of supporting herself and her children and, therefore, in need of help, her image instrumentalized to legitimize New Deal policies. The children depicted seem to have attracted even less attention in photographic discourses.

Furthermore, as Robert Hariman and John Louis Lucaites show, Thompson later in her life appeared “bitter, angry, alienated … by the commodification of her image that completely divorced the woman in the photograph from the living Thompson” (2010, p. 62).

As Hariman and Lucaites also show, however, Thompson evolved from an anonymous, silent and pitiful migrant worker to an articulate woman demanding recognition and acknowledgement thus exerting agency and challenging photojournalistic conventions.

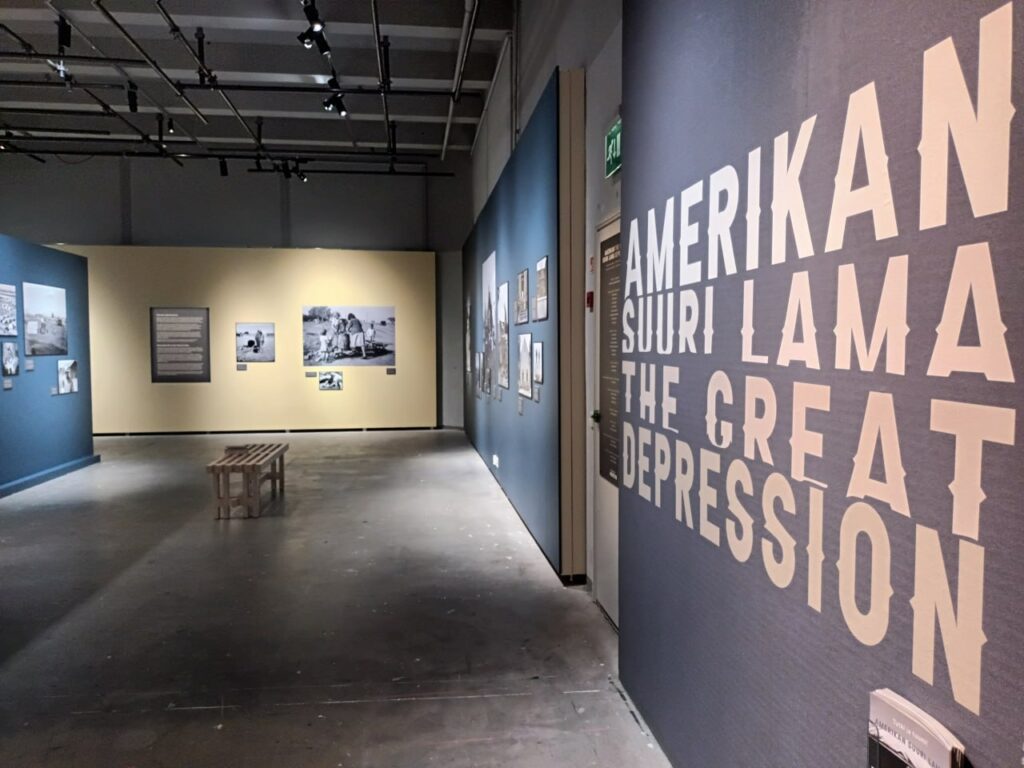

This exhibition at The Finnish Labour Museum Werstas shows Migrant Mother alongside other equally stunning but less famous Lange photographs. The exhibition offers ample opportunities not only to admire Lange’s photographs and the enduring power of the documentary genre, but also to reflect on several questions that keep tormenting this genre – ethical, aesthetic and political questions:

Is documentary photography merely documentary? In other words, what is the relationship between portraying and creating people as victims?

Is “victim photography” (Solomon-Godeau 1991, p. 176), fixing people as victims, ethically acceptable? After all, often it is characterized by aesthetically appealing, perfectly composed representations of human suffering – beauty derived from the pain of others.

Is a viewing position ethically acceptable that derives pleasure from visual representations of people in pain (Bal 2007, p. 103)? What is the adequate moral response to such a viewing experience? Is there an adequate response to such an experience?

Is Lange’s photographic work only of historical relevance or is it relevant also today at a time when migration is once again one of the most pressing and controversially discussed political issues?

Ultimately, is there a danger that photography, rather than raising awareness, contributes to removing such political issues as migration from politics to aesthetics, thus potentially depoliticizing these issues and reframing them in visual-aesthetic rather than political and socio-economic terms?

The Great Depression is at The Finnish Labour Museum (Työväenmuseo) Werstas, Tampere, until 18 August 2024.

References

Mieke Bal, “The Pain of Images,” in Beautiful Suffering: Photography and the Traffic in Pain, edited by Mark Reinhardt, Holly Edwards and Erina Duganne (Williamstown: Williams College Museum of Art/Chicago: The University of Chicago Press 2007), pp. 93–115.

David Campany, “The Migrant Mother,” in Dorothea Lange: Politics of Seeing, edited by Alona Pardo with Jilke Golbach (Munich, London, New York: Prestel, 2018), pp. 21–25.

Robert Hariman and John Louis Lucaites, No Caption Needed: Iconic Photographs, Public Culture, and Liberal Democracy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press 2010), pp. 53–67.

Dorothea Lange, Photographs of a Lifetime (New York: Aperture, 1982).

Frank Möller, Peace Photography (Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019).

Jay Prosser, Light in the Dark Room: Photography and Loss (Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 2005).

Abigail Solomon-Godeau, Photography at the Dock: Essays on Photographic History, Institutions, and Practices (Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 1991).