Memory has become a keyword in the arts, the social sciences and the humanities when addressing the past and its legacies (Salzman 2006). To remember is an individual faculty but, as individuals normally remember as members of social groups, also a collective faculty (Halbwachs 1992). Individual and collective memories do not always coincide; in different social groups, individuals remember differently what seems to be the same event. Likewise, personal and official memories and the narratives derived from and legitimized through them are not always identical. Indeed, there is often a profound tension between what individuals remember and what they should remember according to official narratives. Insisting on individual memories can put people at risk. Memory is politics.

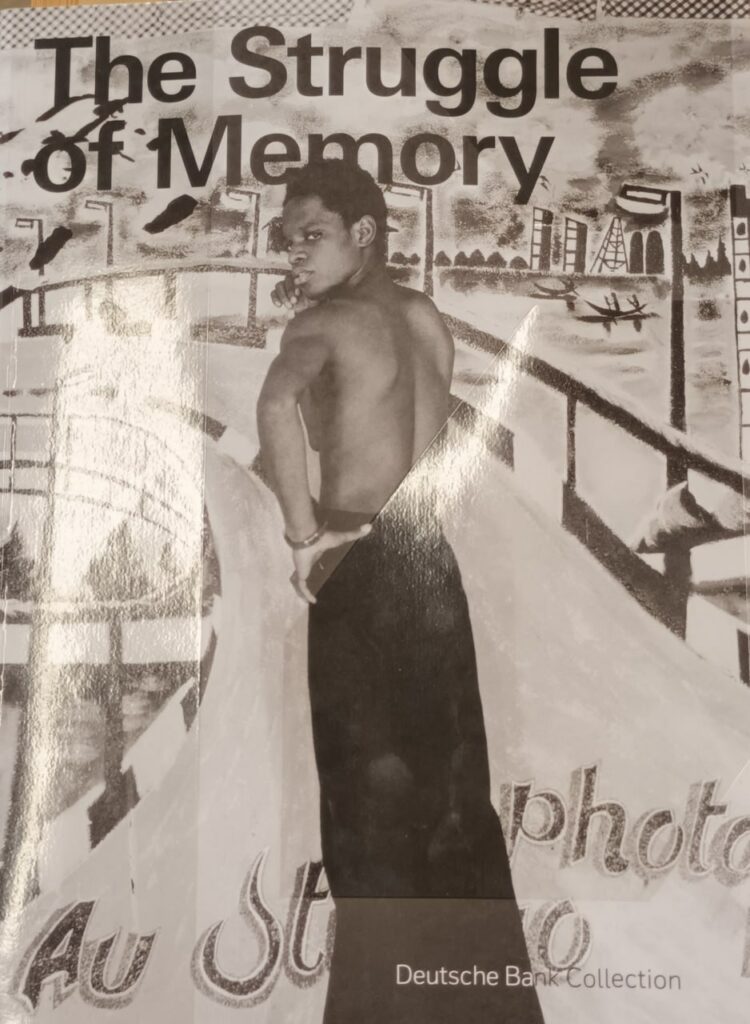

Deutsche Bank Collection, PalaisPopulaire, Berlin

Individuals may feel dispossessed of their memories by official narratives stipulating a different reading of the past. Artistic appropriations, too, can be perceived as violations of and infringements on individual experiences which, after all, are owned by someone and this someone is not normally the artist (Bennett 2005). Memory always competes with forgetting (Rieff 2016) – positioning memory against forgetting is a simplification as both may coincide and perhaps even condition one another – and may be reshaped in light of present requirements. It involves not only remembering but also reinventing the past. People suffering from traumatic reenactment might wish to forget but cannot. People suffering from dementia might wish to remember but cannot, either.

When represented through images and the visual arts, memory tends to fade away, replaced by the image and the memories of the image (Elkins 2011). However, not to forget is a moral claim articulated by victims and scholars in connection with atrocities such as the Holocaust (see Wieviorka 2006). Artists often define their work in these terms, too. Not to forget is a claim also often made in connection with the legacies of colonialism, the history of which has mainly been written by the colonialists themselves with very little regard for local voices.

Remembering colonialism includes remembering, but not idealizing, the pre-colonial past, inventing the alternative history – the what–might–have–been – that could have materialized in the absence of colonialism, and rediscovering local voices who may remember deviating and alternative aspects of colonialism including acts of resistance and everyday coping mechanism. Reclaiming memories, remembering colonialism from the perspectives of the colonized and sharing these perspectives with others is one of the pressing moral imperatives of our times. It certainly is, as this exhibition claims, a struggle but a struggle for what exactly – acknowledgement, recognition, respect?

As the curator of this fabulous show, Kerryn Greenberg, argues in the catalogue, colonialism’s contempt for African civilizations as well as literary and philosophical traditions, triggered and legitimized by racial theories and practices culminating in slavery, coincided with the looting of African art, “illegally acquired in vast quantities by Western museums.” Restitution certainly is a pressing issue, albeit “only one step in a long journey toward the reconstruction of memory and cultural self-reinvention.” Once lost, however, memory cannot simply be reconstructed.

This exhibition is in search of what Greenberg calls “alternative narratives” interrogating “the gaps between what is known, knowable, and unknowable.” The visual element is dominant although memory cannot be reduced to the visual. What we hear and what we smell is as important as what we see to how and what we remember.

Greenberg acknowledges that her catalogue contribution consists of “snippets of ideas connected by associations rather than structured into a linear argument; contingent, precarious, incomplete. Much like the nature of memory itself” – and much like this exhibition, a patchwork (rather small but variegated nevertheless) made up of pieces or fragments co-presented without claiming that the sum of these pieces and fragments would necessarily form a coherent whole.

David Levi Strauss explains that to “be compelling, there must be tension in the work: if everything has been decided beforehand, there will be no tension and no compulsion to the work” (2003: 10). Tensions, ambiguities, juxtapositions, incongruities, gaps, voids and contradictions adequately capture memory as a messy place; its components are often out-of-sync and, even if identified, cannot simply be assembled into a congruent arrangement. Not knowing where they come from, many people are, as Greenberg notes, unable to “adjust to the circumstances of the present and challenges of the future.” Thus, memory’s struggle is not least a struggle for individual and collective places in society as a condition for the possibility of self-determination, culturally, socially, politically, psychologically – and mnemonically.

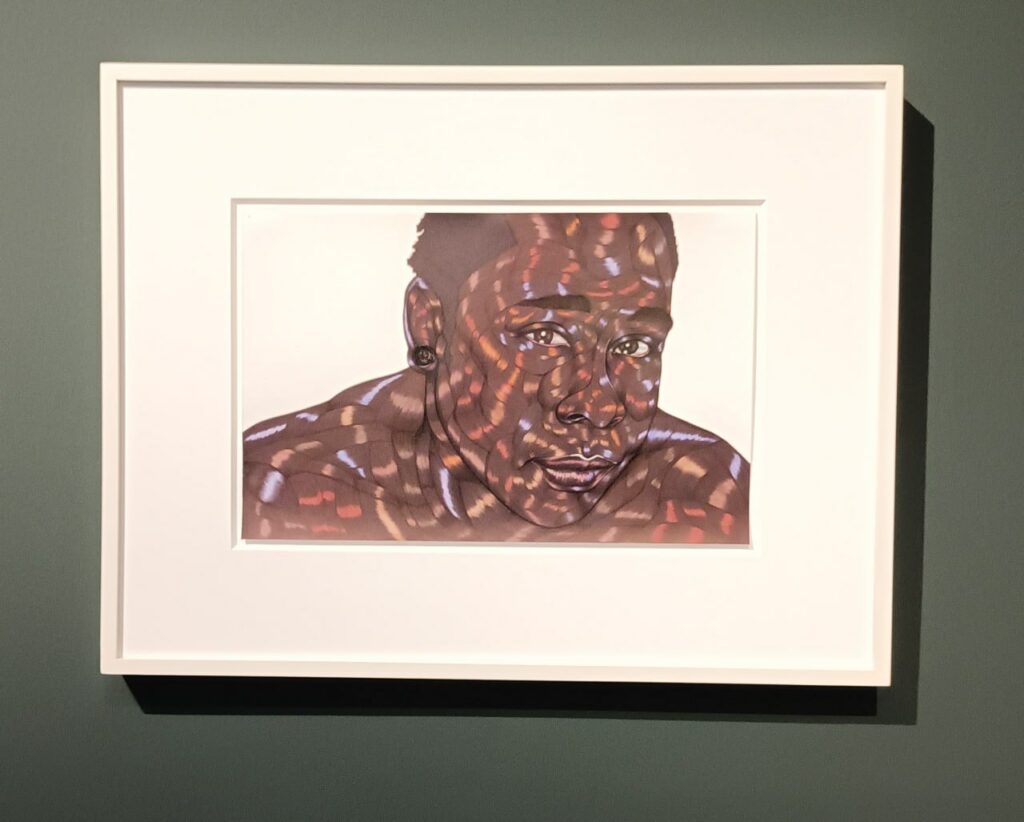

Part 1 of this exhibition brings together artworks that explore, in different ways, how the body absorbs, processes, stores, and recalls experiences. Many of the artists exploit that gap between personal and official narratives, grappling with the precarity of memory and responding to histories of dislocation and loss. Working with fragments and traces, utilizing repetition and shadow play, stressing the importance of language in remembering and resisting, collapsing time, and encouraging us to employ all pour senses to experience and remember, they explore the slippages between fact and fiction, imaginatively reconstructing connections to the past in the void left by history.

From the exhibition:

The Struggle of Memory, Part 1:

Berni Searle

Kara Walker

Samuel Fosso

Mohamed Camara

Lebohang Kganye

Toyin Ojih Odutola

Wanchegi Mutu

Mikhael Subotzky

Anawana Haloba

The Struggle of Memory is at Deutsche Bank Collection, PalaisPopulaire, Unter den Linden 5, Berlin. Part 1: April 19 – October 3, 2023; Part 2: October 20, 2023 – March 11, 2024

References

Bennett, Jill (2005) Empathic Vision: Affect, Trauma, and Contemporary Art, Stanford University Press.

Elkins, James (2011) What Photography Is, Routledge

Greenberg, Kerryn (2023) The Struggle of Memory against Forgetting, in The Struggle of Memory, edited by Deutsche Bank AG and Kerryn Greenberg, Kerber Verlag, pp. 11–23

Halbwachs, Maurice (1992) On Collective Memory, University of Chicago Press

Rieff, David (2016) In Praise of Forgetting, Cornell University Press

Salzman, Lisa (2006) Making Memory Matter: Strategies of Remembrance in Contemporary Art, University of Chicago Press

Strauss, David Levi (2003) Between the Eyes: Essays on Photography and Politics, Aperture

Wieviorka, Annette (2006) The Era of the Witness, Cornell University Press.

Photography © Frank Möller