At the end of the year, reflections on The End of the World – Alfredo Jaar’s new engagement with the capitalist-militarist exploitation of minerals. This exploitation is indispensable to digitisation, the data-based society, energy transition and ostensibly green economies. Combining private capital with state security interests, it results in intensified, ruthless violence exerted on both human beings and the natural environment, turning Earth into waste and treating human beings as dispensable, sacrificed for the pursuit of profit and national security.

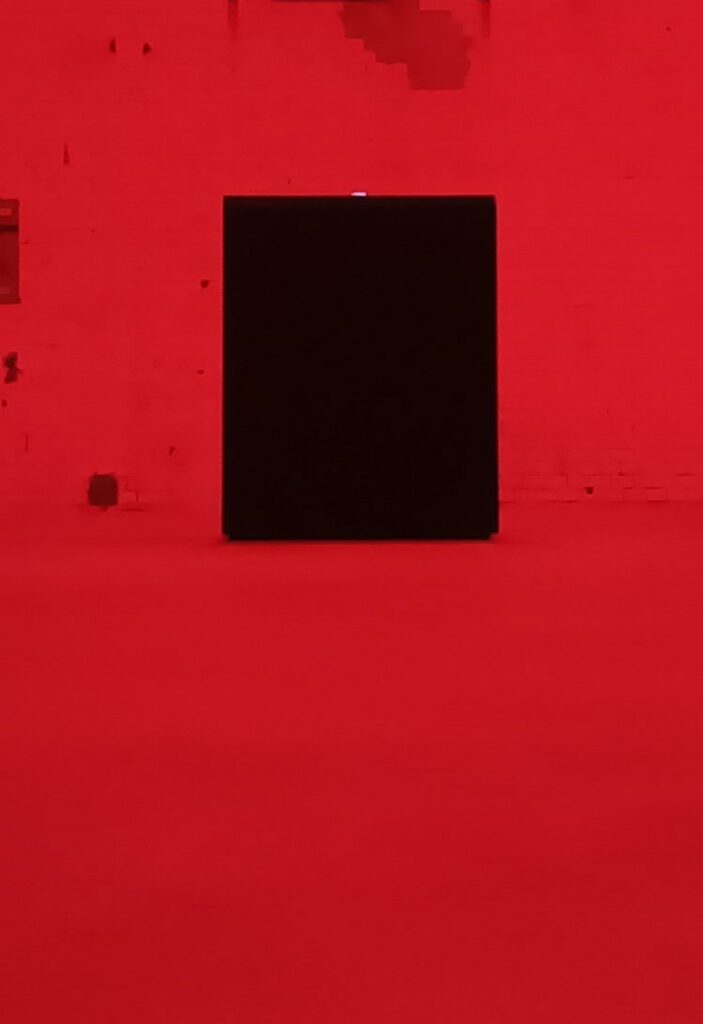

The exhibition, curated by Kathrin Becker, is on display at and tailored to the specific features of the KINDL – Centre for Contemporary Art’s marvellous Kesselhaus in Berlin.

The Kesselhaus – measuring 20 x 20 x 20 metres – is indeed an impressive venue for large-scale installations and installations reflecting on the most pressing issues of our time. As Becker writes: “Drawing on five years of research, he [Jaar] offers his insights into the ecological and political crises of the present and the future,” especially “exploitative mining practices and the relentless pursuit of profit.”

It is not the first time that Jaar engages with what Adam Bobbette, in the exhibition’s brochure, calls “mining … and its violence.” In 1985, for example, Jaar thematised working conditions in the gold mines of Brazil, juxtaposing images and text in such a manner that “apparently separate realities” are connected with one another, thus revealing complex and often invisible structures: “the miners in the depths of Amazonia exposed not just to the vagaries of their job but also to those of the market, the clearly marked geography of a gold mine and the network of exchange and profit in the financial capitals of the North.”¹

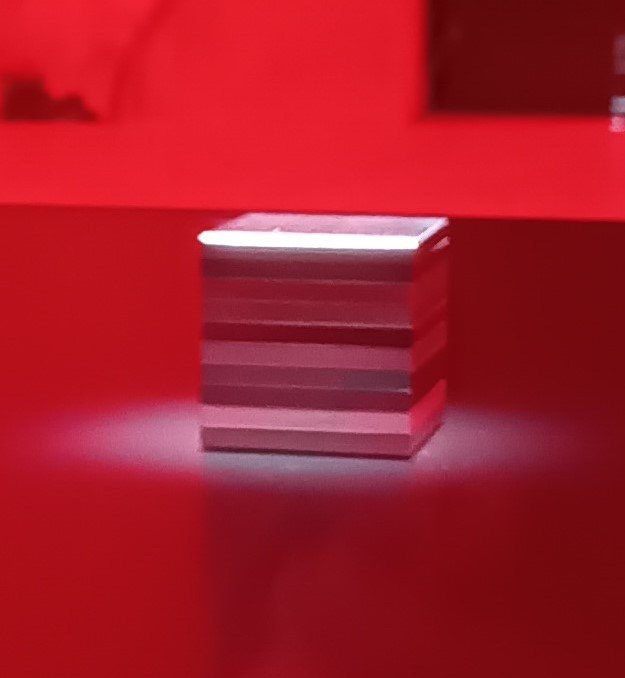

Yet, although presented in the Kesselhaus’s impressive exhibition space and referencing a very complex subject, The End of the World is anything but large: its oak base measures 2.5 x 75 x 75 centimetres; its plexiglass vitrine 75 x 75 x 75 centimetres and its wooden pedestal 90 x 75 x 75 centimetres – a miniscule project, almost disappearing in the huge exhibition space. As Becker explains:

“Within the expansive Kesselhaus, the installation demands focus on a 4 x 4 x 4 cm cube composed of layered raw materials: cobalt, rare earths, copper, tin, nickel, lithium, manganese, coltan, germanium, and platinum – ten strategic metals vital to digitalisation, electromobility, high-tech applications and storage media.” In the insightful essay, Bobbette describes the devastating effects the “violence of mining” has for both human beings and the environment, none of which can be seen in Jaar’s project.

The project is one of abstraction and juxtaposition, confronting, as Becker explains, “the elegant presentation of the object, reminiscent of a jewellery display” with “the ‘dirty business’ of its extraction” and “the emptiness and silence of the darkened Kesselhaus” with “the explosive nature of the subject matter.”

Abstraction is not without risks, however, “always provisional and contingent upon the cultural norms that are being challenged”² and the observer’s willingness to engage with the artwork’s subject matter. To some observers, Jaar’s installation may appear beautiful but ultimately irrelevant in light of what Becker calls “the immense scale of the ecological, social, and political upheavals it represents”; others may wish not only to enjoy the artwork but also to engage with that which it claims to reference.

Change of scale is key here. As Roland Barthes reportedly suggested, change of scale “disrupt[s] familiar perception” thus “transform[ing] the power of attention and observation” and creating a “new order of experience”³ – a new order that also capitalises on the beauty of the installation.

This beauty might seem problematic when compared with the living and working conditions of the miners. “Beauty,” Mieke Bal notes, “distracts, and worse, it gives pleasure – a pleasure that is parasitical on the pain of others.”⁴

But this is not the only function of beauty. The beauty of the installation – its striking red colour illuminating the Kesselhaus’s rough, unrenovated walls – may equally well evoke feelings of anxiety and uneasiness on the part of the observer.

Such feelings may be triggered by the extent to which each observer is involved in the digital society by, for example, taking pictures by means of a camera phone thus, as Bobbette’s essay unmistakably makes clear, benefitting from and participating in the exploitation of others. This may be even more so for those observers who visit the Kesselhaus by means of an electric vehicle which arguably is one of the most visible symbols of mining and its violence.

The End of the World also shows the complexities of peace and its visualisations – complexities that we tried to address in our most recent book (Peace, Complexity, Visuality: Ambiguities in Peace and Conflict) and in the blog posts published on this website, including guest contributions. At the end of the year, we would like to thank Dagmar Punter for her thoughtful and thought-provoking contributions and you, our readers, for your continuous attention to, engagement with and interest in the visualisation of peace.

We wish you a pleasant and peaceful festive season.

Alfredo Jaar’s The End of the World is at KINDL – Centre for Contemporary Art, Berlin, until 1 June 2025.

More information on the website of KINDL.

More information on the website of Alfredo Jaar.

¹ Nicole Schweizer, “An Open Work – A Non-stop Record, selected works 1985–2007,” in Alfredo Jaar, It Is Difficult, Vol. 2, edited by Gabi Scardi and Bartolomeo Pietromarchi (Verona: edition Mantua, 2008), p. 135.

² David Campany, “What on Earth? Photography’s Alien Landscapes,” Aperture 211, Summer 2013, p. 51.

³ Michael Sheringham, Everyday Life: Theories and Practices from Surrealism to the Present (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), p. 194 and p. 193.

⁴ Mieke Bal, “The Pain of Images,” in Beautiful Suffering: Photography and the Traffic in Pain, edited by Mark Reinhardt, Holly Edwards and Elina Duganne (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007), p. 103.

Photographs taken at the exhibition for strictly informational and non-commercial purposes.