Given the forum that this blog post[i] is written for I should state straight away that I consider the arts (visual and performative) to be a form of communication and to have the same kind of transformative power that the more ordinary forms of communication (talk, writing, news media) have. In this I follow Cooley and Dewey – the latter argued that art was the ‘most universal and freest form of communication’, one that is able to break ‘through barriers that divide human beings, which are impermeable in ordinary association’ (Dewey 2005[1934]: 254). Others have argued that art ‘can influence the way people interpret, perceive, and ultimately act in their communities’ (Hawes 2007: 18), ‘communicate and transform the way people think and act’ (Shank and Schirch 2008: 218). Overall, what ‘is expressed within the imagination of art simultaneously constitutes and is constituted by the society; both a reflection of society and a key agent of its transformation’ (Premaratna 2018: 8). It is particularly effective when words don’t seem to be able to capture experiences, trauma, wishes and desires. Understood in this way, the arts are fundamental to and constitutive of civil society and as such, cannot be dismissed as entertainment or ‘add-on culture’; as something peacebuilding missions do not need to prioritise.

I believe that the way in which peacebuilding missions fail to understand the fundamental importance of communication[ii] (widely conceived to include the fictional and factual media as well as the visual and the performative arts) has decreased the chances for self-sustainable civil peace; that is societies’ ability to peacefully cooperate despite deep disagreements. In my recent book I chose to make my argument about the fundamental importance of communicative peacebuilding by focusing on post-civil war settings. This choice was made simply because such settings provide the perfect imperfect conditions to illustrate my argument but they are by no means the only settings to which it applies.

Communicative peacebuilding: discursive civility

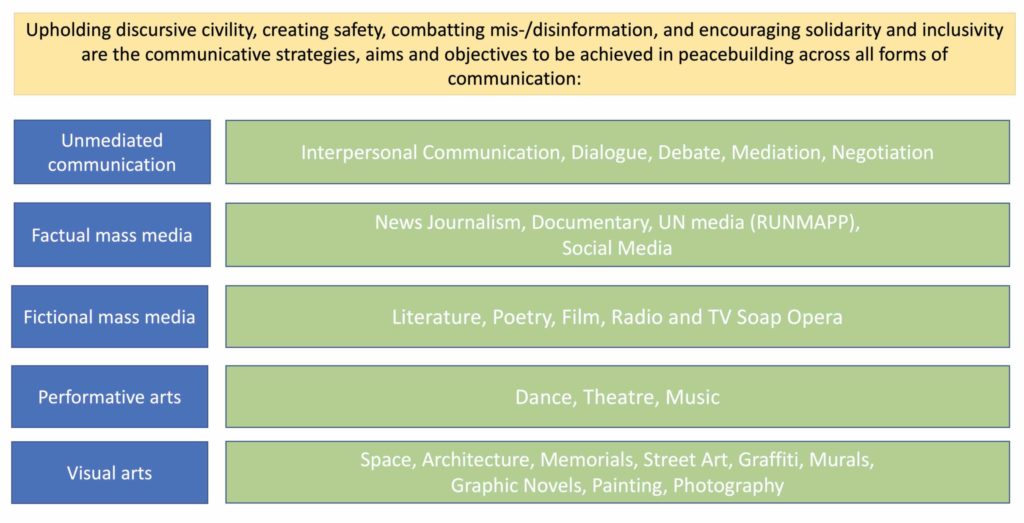

The aim of communicative peacebuilding is to use communicative activities across the spectrum of civil society both offline and online/digital in polarised, conflict-affected and post-conflict settings to rebuild the capacity for and instantiate peaceful cooperation, to support the development of both the relationships and the socio-cultural transformations necessary to move from enmity to co-citizenship. Peaceful cooperation here is understood to be based on the performance of three categories of civil norms: a) assent to civil peace, that is the desire to build peace, to engage with the past and conflicting histories/experiences all by being future-facing; b) substantive civility which is related to the way in which citizens conduct themselves; one that can generate trust and solidarity. It is concerned with cultivating a public good; the acknowledgement of the equal civil standing of all members of society and behaviour that reflects this; a regulator of relationships between citizens including the ways in which disagreements and disputes are carried out between citizens. Finally, c) building capacity and citizens’ competences – especially the ability to associate, to form coalitions and to learn the art of collaboration.

To achieve such civil peace as peaceful cooperation, two elements are indispensable in communicative peacebuilding: a) the upholding of the three principles of discursive civility – in other words and simply put, the linguistic tools needed for communicative engagement to remain non-violent and agonistic in the face of hostility and deep divisions; b) the building of safe discursive spaces in which such communicative engagement can be safely undertaken.[iii]

The three principles of discursive civility that ensure that any communicative engagement remains safe and peace-oriented are:

- Principle 1: Participants have to make a commitment to manage their individual negative emotions (emotional forbearance)

- Principle 2: Participants have to make a commitment to both listen to the other and importantly to hear the other (perspective-taking)

- Principle 3: Participants have to commit to making only such contributions that are supportive of the pursuit of peace (reasonableness)

These three principles do not prescribe content but rather they guide how something can be expressed and how communicative engagement proceeds. It is also a tool that aims to moderate viewpoints as the aim of any communicative engagement is the rebuilding of peace and peaceful cooperation. The principles of discursive civility help to depolarise and to create a safe space for communicative engagement both offline and online. They can be locally and culturally interpreted in different ways, but they are the universal standards that ensure that disagreement and difference can be dealt with in non-violent and agonistic ways. Without the principles of discursive civility there is no civil peace as peaceful cooperation. These three principles also serve as a form of guarantor for safe communicative engagement with former enemies.[iv]

Discursive civility and peaceful cooperation in the visual arts

Each communicative activity shown in the figure above can interpret and uphold the principles of discursive civility in its own ways. For example, the visual arts (including memorials, photography, architecture etc) ‘can contribute to creating both imaginative and realistic environments that invite or encourage viewers to step into other worlds, to go beyond historic divides and to imagine why a peaceful future is worth working for’ (Mitchell 2020: 61), ‘may contribute to mutual responsiveness’ and ‘thwart the transformation of difference into Otherness’ (Möller 2017: 323f). Photography, in particular, has been seen as able to ‘help transform spectators into participant witnesses who, by looking at art photography, become aware of their own involvement in the scenes depicted’ (Möller 2010: 131). In societies that aim to rebuild themselves in a post-civil war setting, ‘the visual arts are an expression of the aspirations of people in their hope for a more [peaceful] (…) society. It emphasizes the power and potential of collective voice in the visual portrayal of historical injustice and the envisioning of a new [future]’ (Berman 2017: 1) yet to be created through ‘imagination, play, innovation, and skills’ and the provision of safe discursive spaces to enable ‘new ways of seeing’ (ibid.: 7).

What does peaceful cooperation through the visual arts look like and how can the arts uphold the three principles of discursive civility? Communicative peacebuilding that aims to help rebuild peaceful cooperation through the visual arts operates on three levels: the production of the piece of art; the piece of art itself and the audience. The production of a photography project or a memorial starts with the production team that needs to peacefully cooperate across the three categories of civil norms and to uphold the three principles of discursive civility when deciding to work together (collaborators might be former enemies) as well as deciding what kind of art to be produced, what meaning to be expressed, which materials to be used, which locations to be chosen. The photography or memorial themselves need to represent and exemplify these three categories of civil norms of peaceful cooperation through the materials used, the location chosen, the objects/subjects portrayed, the inscriptions etc. And the visual arts also have to display the three principles of discursive civility – how is anger and blame dealt with in the piece of art? In which ways can it be understood to display a future facing attitude and the acknowledgement of the equal civil standing of the other as well as does it possibly portray a common good, the need to collaborate and associate? How does it listen or engage in perspective-taking? And finally, there is the audience – the audience enacts the three categories of civil norms of peaceful cooperation in the way it engages with the visual arts and upholds the three principles of discursive civility in the way it engages with it, thinks about it and looks at it.[v]

When peaceful cooperation is naturally instantiated and when the three principles of discursive civility are upheld across these three levels of engagement all artificiality disappears and the engagement becomes and is experienced as authentic. When this happens, we can start speaking of a transformative communicative act; one that has achieved a reimagination of the former enemy as a co-citizen. It is at this point that communicative peacebuilding can have real and lasting impact: supporting civil societies in the move from enmity to co-citizenship.

About the Author

Stef Pukallus is a Senior Lecturer in Public Communication and Civil Development at the University of Sheffield (UK) and founding chair of the Hub for the Study of Hybrid Communication in Peacebuilding (HCPB). Her research interest and expertise focus on the role that public communication can play in the building, development as well as in the diminishment and destruction of civil societies (emergent and mature). She has just published her third research monograph entitled Communication in Peacebuilding: Civil Wars, Civility and Safe Spaces (published with Palgrave Macmillan).

[i] This blog post is based on Pukallus, S. (2022) Communication in Peacebuilding. Civil wars, civility and safe spaces. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

[ii] One example of this narrow vision of communication can be seen in the way news journalism is understood: as an information provider that simply exists to ensure the success of the first democratic post-conflict elections and therefore of the peacebuilding mission. What such peacebuilding missions fail to understand is that news journalism is a civil institution and that it also has a civil norm building function. It cannot be reduced to a means to an end because if and when it is, peacebuilding missions fail to create an institutional lasting structure and thereby do not contribute to the empowerment of civil societies to build self-sustainable civil peace; peace that lasts beyond the peacebuilding mission.

[iii] On b) see Pukallus (2022).

[iv] They underpin safe discursive spaces.

[v] For detailed examples see Pukallus (2022, Chapter 5).

Bibliography

Berman, K. (2017). Finding voice: A visual arts approach to engaging social change. University of Michigan Press.

Dewey, J. (2005[1934]) Art as Experience. New York: Perigee.

Hawes, D. (2007) Crucial narratives: performance art and peace building. International Journal of Peace Studies, 12(2): 17-29.

Karlberg, M. (2005) The power of discourse and the discourse of power: pursuing peace through discourse intervention. International Journal of Peace Studies, 10(1): 1-23.

Keith, W. and Danisch, R. (2020) Beyond Civility. The competing obligations of citizenship. Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Mitchell, J. (2020). Peacebuilding through the visual arts. In J. Mitchell (Ed.), Peacebuilding and the arts (pp. 35–70). Palgrave Macmillan.

Möller, F. (2010). Rwanda revisualized: Genocide, photography, and the era of the witness. Alternatives, 35(2): 113–136.

Möller, F. (2017). From Aftermath to Peace: Reflections on a Photography of Peace,” Global Society: Journal of Interdisciplinary International Relations, 31(3): 315–335.

Premaratna, N. (2018) Theatre for Peacebuilding. The Role of Arts in Conflict Transformation in South Asia. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Shank, M. and Schirch, L. (2008) Strategic arts-based peacebuilding. Peace & Change, 33(2): 217-42.